For as long as I can remember the defining qualities of a good person seemed obvious: competence and integrity. Competence not only contributes and makes possible, but reduces mistakes, inefficiencies, and unfair burdens. Integrity not only underpins ethics and guides competence, but reduces distrust, hostility, and selfishness. Competence and integrity give to the world while their opposites drain from it.

These qualities demand a lot of individuals. They must learn to delay gratification and endure discomfort, inconvenience, and difficulty. They must develop high standards, be self-critical, respect truth, and loathe excuses. They must prioritize performance and potential over perceptions, emotions, and costs.

These qualities bring risks to society. Competence unbalanced by other considerations is, among other things, dangerous.1Psychopaths offer an extreme example of this. Integrity unbalanced by other considerations is, among other things, impotent. And many otherwise reasonable combinations are, among other things, overconfident and judgmental.

It is a challenge to embrace these qualities despite their arduous nature and to intertwine their development with enough wisdom to apply and balance them well. This challenge is at the core of classical philosophy. It is prominent in religion, military, science, and engineering. It animates intensive educational experiments by the likes of James Mill, Bertrand Russell, Leo Wiener, and Laszlo Polgar. It finds expression in the idea of the New Soviet Man. Its essence is to instill maximal striving to develop one’s potential, live honorably, and contribute to a larger purpose – and to organize society to aid in this task.

This goal depends on assumptions. It presumes existence of better and worse, possibility of agency and coherence, inescapability of causation and responsibility. Its implementation ties worth to choices and promises evaluation on the basis of efforts and achievements.

On these foundations it erects the expectation of judgment and the desire to prove oneself. It then provides tools to do one’s best: to strive for perfection and accept responsibility; to focus on understanding how things work; to control impulses that might lead one astray; to think carefully about intentions and take care in action; to find it dishonorable to hide behind excuses and ignorance or to get away with carelessness and incompetence. It fundamentally depends on, and encourages, individual pride based on contribution, integrity, and effort.

There are many disagreements about implementation details, but they mostly share prerequisites. And each of these prerequisites has come under growing scrutiny over time. It increasingly feels like the ethos itself is under an unrelenting attack from all sides. And perception of such attacks seems to underlie many vicious disagreements of our time.

These attacks are rooted in societal and personal risks, justified through postmodernism, and emboldened by prosperity.

Attacks on Competence and Integrity

Attempts to implement visions of better and worse have been fraught with authoritarianism and abuse. And people of competence and integrity have been used to advance agendas of unscrupulous leaders. 2Orwell’s fictional account of the hapless Boxer in Animal Farm is based on the competence-focused Stakhanovite movement of the nascent New Soviet Man era.

We can blame gullibility of loyal workers for enabling abuse and choose to encourage less perfectionism and more rebellion, but we can also blame immorality of the leaders and choose to emphasize importance of moral education. We can accept amoral, competitive interactions between different interests and choose to embrace self-centered solidarity regardless of its justification or optimality,3Scott Alexander’s post on mistake theorists highlights the logic. but we can also notice the pull manipulation has over emotional and self-interested masses and come full circle to blame those traits for empowering unscrupulousness in pursuit of influence.

Leadership abuses allow us to blame competence and integrity for horrific events. But they also offer reasons to double-down on these qualities among experts, leaders, and everyday people.

Leadership abuses aren’t the only risk. Competence enables and accelerates progress, but progress has brought with it a long list of ills from the rat race to alienation, from complexity to rapid change, from loss of meaning to existential risks.

These challenges allow us to blame competence and integrity for competitiveness, callousness, fragility, confusion, and stubbornness we see. But they can also push us to emphasize the importance of those very qualities for solutions.

Still, if the purpose of progress is to enable comfortable, happy lives then it seems reasonable to enjoy comforts available today instead of pushing ever further – even if we accept this as being unfair to our predecessors. Plus by striving less we won’t make things worse.

But it is also reasonable to argue that such hedonism and risk-aversion robs our successors of a still better life and that resulting incompetence places unfair burdens on our contemporaries.4These days it is fairly common to be reminded – correctly – of contributions from flawed people and taken-for-granted jobs. But the offsetting impact of unwitting mistakes made by flawed people and contortions made necessary by their limitations are rarely mentioned. Since most impactful discoveries hide at the limits of human ability and societal capacity, anything that limits competence has an unknowably massive potential cost.5Bruce Sterling cleverly distinguishes commendable frugality from risk-averse obsession with not making things worse by asking whether your dead great-grandfather is doing the task better than you. The goal should be to maximize your resource-adjusted contribution, not to minimize your resource use.

We could counter that this trade-off will exist as long as there is progress and we should not make ourselves slaves to the means when we can enjoy the ends. But we could also emphasize curiosity and striving as quintessential human qualities that offer a nobler path to happiness and defend the process of discovery, understanding, and improvement as a worthy end in itself – with positive external effects merely adding to its superiority.

Such concerns and choices about societal progress interact with questions targeting individual excellence and pride.

High standards threaten risk-aversion, closed-mindedness, burn out, and extremism.6Engineers, for example, are susceptible to terrorism and conservatism. We can downplay perfection to encourage open-mindedness and creative risk-taking, but we can also attempt to mitigate the risks with even higher expectations and even more sophisticated capabilities.

Pride makes compromise and teamwork difficult. We can treat getting along as an essential skill, but we can also try to engage the energy and perfectionism of pride through teams with shared values.

Striving is judgmental: it evaluates and ranks the quality of effort, the extent of accomplishment, and the importance of endeavors. We can emphasize tolerance, sympathy, support, and self-love, but we can also strive to develop abilities to accept judgments productively and emphasize the importance of making them fair.

Who has the right to judge which skills and endeavors are better anyway? And who can accurately assess the peculiar circumstances of others and hence the quality of their effort? Such thinking tempts authoritarianism and has been responsible for all manner of gross injustices. We can simply discourage judgments, but we can also keep trying to resolve these challenges.

And isn’t happiness the point anyway? If pursuit of excellence and pride threatens stress, exertion, conflict, loneliness, and unhappiness then why do it? We can reject happiness as the ultimate purpose or claim that pride and accomplishment are necessary for truly human flourishing. But we can also endorse baser happiness to make it more accessible. We can strive to become what Nietzsche predicted and feared most: last persons.

Every societal and personal concern can be answered at least as well by increasing the importance of competence and integrity as by diminishing them. This is where doubt that postmodern arguments slip into concepts like truth, coherence, agency, goodness, responsibility, and purpose is necessary to legitimize lapses in competence and integrity – or to undermine the superior standing competence and integrity requires to be taught.

The practical reality is that most living beings will take the easiest defensible path available to them. It takes concerted effort to curtail ignoble paths and to promote temperament and skills to resist natural inclinations. Yet the trend has been towards isothymia – the desire to be recognized as equal on the basis of being human – at the expense of megalothymia – the desire to be recognized as superior on the basis of accomplishment.7Francis Fukuyama presents a compelling case for desire for recognition being a major driver of individual action and human history starting with The End of History and the Last Man through Trust and Origins of Political Order. His recent Identity offers a more compressed, updated, and accessible presentation. This trend – even if well-justified – legitimates easier paths, lowers expectations and abilities, and expands and empowers the coalition of the happily incompetent last persons which then works to legitimate still lower standards.8See Irving Kristol’s lucid “Republican Virtue vs. Servile Institutions” in The Neoconservative Persuasion.

Above arguments and choices aren’t new. The contemporary trend is aided by success of markets that are increasingly viewed in amoral, impersonal, aggregate terms that make individual choices feel unimportant. And by large-scale failures of authoritarianism and visible risks of technocratic progress.9Early portion of The Existential Pleasures of Engineering offers an engaging account of such risks and the shift of focus towards them. Yet the impact of these would remain limited without prosperity.

Prosperity reduces the need for conventional competence and integrity in everyday life. It disconnects an increasing number of people from realities of accomplishment and replaces these with management of perceptions. It encourages taking for granted that things work. And it provides time, resources, and motivation to attack every conceivable inconvenience and injustice regardless of effect on function.

Political Compass

Scott Alexander models much of this with his Thrive/Survive theory. Necessity pushes the Survive side to value competence and loyalty while abundance frees the Thrive side to focus on pleasure and perceptions.

The Thrive side seems to feel no sense of indebtedness for fruits of progress it receives. Resources of post-scarcity are to be used in the easiest and most direct pursuit of happiness via hedonism and status games. Thrivers seem to feel no pride in integrity, duty, excellence, perseverance, or contribution to a larger purpose. They seem to have no interest or ability to take serious risks, endure significant discomfort, or understand complex systems. They have pride and value competence primarily in the context of winning sufficiently riskless status games and are thus scarcely distinguishable from last persons.

The Survive side seems restricted to scarce environments and unconcerned with the world beyond their community. But their approach is beneficial not only for “tiny unstable bands facing a hostile wilderness,” but for groups that make up any organization concerned with effectiveness.10Fukuyama explores this in Trust: The Social Virtues and The Creation of Prosperity. It has been the dream of many to supplement competence, drive, and integrity with post-scarcity resources and thus unleash human potential through society-bettering discovery, innovation, and insight – or through individual pursuit of perfection.

Survivors and utopians envision a world not without status, but without status games. Status is essential for teaching and rewarding competence and integrity, but it must be legitimately and honorably earned, not smuggled in with management of perceptions.

Perhaps we just need to add concern with others to this model. Perhaps then Thrivers will feel a sense of duty and desire competence for communal projects as idealists hope. Perhaps then Survivors will feel a connection with outsiders and have it influence their sense of integrity and application of competence. John Nerst’s Political Compass does this by adding a Coupled/Decoupled dimension to measure responsibility to people outside one’s direct relationships.

The combination of Thrive and Coupled engages competence and integrity for optimistic world-building. It believes in systems and fundamental goodness of human nature. It treats the downtrodden as victims of unfair circumstances and considers helping them an obligation. It has a Bright mindset.

The combination of Thrive and Decoupled rejects social engineering and is hesitant about concepts like better and worse. It gives resources because more agency and happiness is better and because they are available. If people choose hedonism and status games then so be it.

Neither of them is too concerned with abuse of charity or with development of individual competence, responsibility, and integrity. The Coupled side believes that people will naturally blossom as unfair systems improve and take proper care of them. The Decoupled side is content to say that these qualities have risks, haven’t been in short supply, and are aided by freedom.

To the extent that ethics, integrity, and competence can be developed, this development is a major portion of the golden goose Scott identifies as being milked by the Thrive side.

The Survive side is intensely focused on individual conscientiousness and concerned with anything that may legitimize large-scale excuse-making. Help isn’t owed by default; those who need it must make their case. This generally requires charity to be on the scale that can reasonably assess individuals and track legitimacy of their pleas.

The combination of Survive and Decoupled optimizes for competence, responsibility, and success on the small scale. It has a Free mindset.

The combination of Survive and Coupled adds the impetus to care about, and contribute to, the larger world. Responsible, competent people working towards a better world and society reciprocating with recognition and support seems the epitome of progress and fairness. Yet Nerst sees fascism, Sparta, small-town conservatism, and the otherwise discontent. These possibilities belong there, but focusing on them is a risk-averse choice that attacks competence and integrity.

Pride and Progress

Developing competence is hard and execution is risky. If it is incentivized economically it encourages selfishness and conflicts with integrity. To be ethically directed towards the world it needs to be encouraged with recognition. When we place it on equal footing with easier choices and prioritize punishing negative potentialities we cannot be surprised that people run away from responsibility and seek refuge among last persons11The Real Problem at Yale Is Not Free Speech offers a wonderful description of how detachment from reality and avoidance of responsibility are seeded, nurtured, and entrenched; and how the assimilated think, act, and perceive themselves. – or spend creative energies to serve and manipulate their growing horde.

As C.S. Lewis quipped in The Abolition of Man:

“We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

The project of constraining ambition and fanaticism because they have societal and personal risks has gone on to be pitted against the project of creating ambition and integrity because they are the source of excellence and ethics. Freedom brought by rational Enlightenment values has gone on to attack the foundations of reason. Prosperity brought by technological progress has gone on to be used against the source of progress itself.

Last persons replace pursuit of competence, contribution, and integrity with one of comfort, support, and happiness. Their position is necessarily entitled and contemptuous of heroes. It stomps on much that is precious and hard-earned. It robs those who chose nobler paths of justly earned recognition. It creates something shallower, more fragile, and less capable. But its appeal is obvious and it has no trouble amassing support.

I am ultimately less interested in political and economic models than in models individuals use to define a good person, motivate action, and constrain behavior. These models get constructed from a jumble of interconnected assumptions and are difficult to pin down. Yet they are crucial because they ground judgments of individuals, groups, policies, and events.

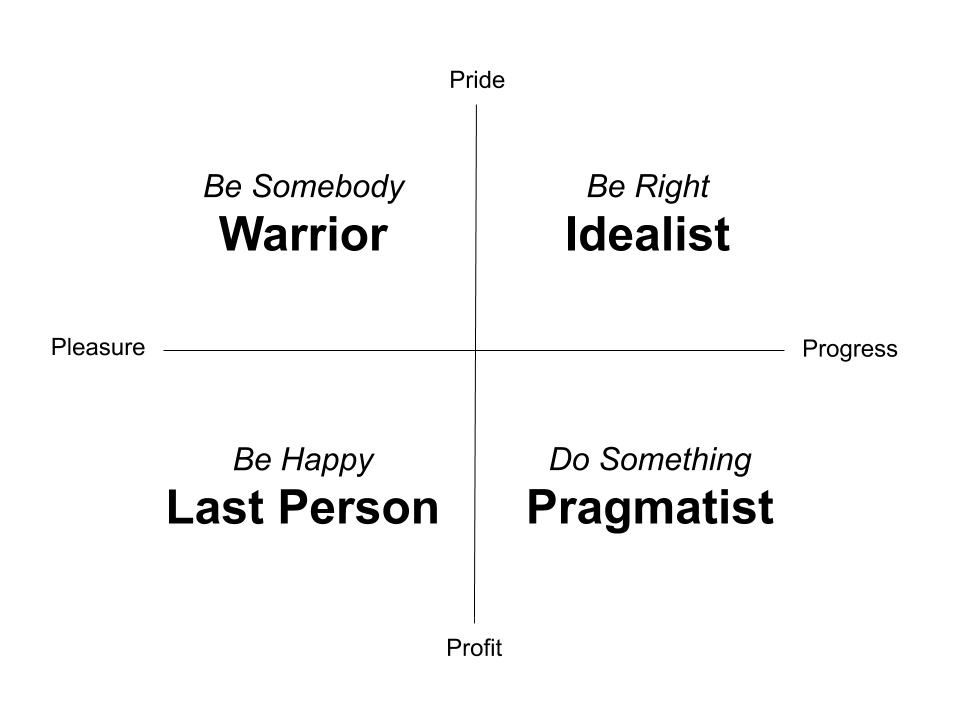

It seems to me that essential differences come down to two clarifying dimensions: perspectives on pride and on progress.

The pride I have in mind is megalothymia – wanting to be the best and be recognized as such – rather than more modest isothymia or dignity. While dignity can be granted to everyone, satisfaction of megalothymia must be earned. Achievement ties megalothymia to judgment and competence, to truth and a sense of honor. Opposing it are perspectives that value peace and comfort, perceptions and pragmatism.

The dimension of progress concerns belief in the possibility and desirability of improvement and in the importance of contributing to it. The progress I have in mind extends beyond individual achievement: it seeks to improve missions, practices, communities, etc. rather than oneself. Progress depends on achievement and is thus tied to competence and truth. But it also depends on group coordination and individual sacrifice. Opposing it are perspectives that embrace pleasure over contribution, meaninglessness over purpose, and the present over the future.

Together these give us the motivational compass:

The Warrior quadrant elevates individual excellence, integrity, and pride. The subtleties of larger mission aren’t that important. This could manifest in wealth or status seeking, pursuit of excellence in domains of dubious value, unethical competitiveness, or extremely ethical ineffectiveness. But it also drives maximal effort, choice of most difficult fields, and heroic self-sacrifice when those actions feed individual’s self-perception. Conversely, sacrifice of integrity for pragmatic considerations would be ignoble and sacrifice of pride for communal progress would be difficult. It could be said that the primary motivation is to earn a particular hard-fought identity: to Be Somebody.12The distinction between Being Somebody and Doing Something comes from John Boyd though my use of terms is a bit different. Boyd’s dichotomy always spoke to me yet felt off as a general model because it merges integrity and contribution into Doing Something. A goal like being a principled person has no clear home. Boyd would be more of an Idealist in my model. Still, I cannot resist the use of his terms.

The Pragmatist quadrant elevates mission progress. Individual integrity and pride, as well as long-term coherence and consequences, aren’t that important. This could manifest in uninspired practicality, unethical methods, short-sighted choices, or unsentimental callousness. But it also drives flexible solutions, difficult compromises, and selfless sacrifices13A quintessential example of pragmatic self-sacrifice is acting without hope of recognition: “one can do a great deal of good in this world if one doesn’t care who gets the credit for it.” when those actions aid missions the individual buys into. It could be said that the primary motivation is to make a difference: to Do Something.

The Idealist quadrant elevates pursuit of excellence in most useful, other-focused domains. Simply being good at something isn’t that impressive. And it elevates progress in such domains when done with maximal possible integrity. Simply achieving progress isn’t that impressive. Idealists seek to do the best thing, in the best way, and for the best reason. This could manifest in analysis paralysis, naivete, exhaustion, complexity, and extremism. But it also drives innovative solutions, principled behavior, and long-term focus. It could be said that the primary motivation is to find the best solution: to Be Right.14I discussed the conflict between Being Right and Being Happy in Two Paths Towards Happiness.

Incompatible perspectives on pride and progress make understanding and cooperation between quadrants difficult. Pragmatists get exasperated that people can be dumb enough to act against their own interests, seemingly unaware that doing so is the essence of having principles and that recognition of honor in these actions is crucial.15The proud choice behind “unreasonable” values and efforts of individuals, and the importance of its recognition, comes through well in this review of Hillbilly Elegy. Warriors exhaust themselves in refusal to yield and are aghast to find themselves proclaimed foolish, lucky, or responsible for second-order effects, their triumphs taken for granted or treated as mere pawns in callous conquering games. And Idealists crucify themselves upon the true and the possible only to be casually dismissed because power dynamics, psychological limitations, existing relationships – or simple laziness, stupidity, and selfishness – make worse better.

As difficult as understanding is, its lack isn’t the main problem. Pragmatists are capable of grasping pride and many have worked out ways to use it for pragmatic ends. Warriors can comprehend the influence of large-scale, pragmatic forces and many mature into mercenaries. And Idealists eventually encounter obstacles insurmountable with their tools and reluctantly tour neighboring quadrants.

But none of them can accept such values as equally legitimate without undermining themselves: their action hierarchies rest on deprioritizing those alternatives. Instead, enlightened Pragmatists use the moral language of non-judgment to frame manuals on manipulation. Mercenaries focus on integrity in professionalism. And Idealists passionately and persuasively justify the necessity of their transgressions.

The side-effect of such arguments is the diminished perception of absolute worth of pride so important to Warriors, of progress so important to Pragmatists, and of optimization so important to Idealists. This doubt pushes each to be less diligent in exemplifying, promoting, and teaching their values. Competence and coherence, conscientiousness and contribution, goodness and responsibility, virtue and truth increasingly seem like mere choices without privileged standing.

The Last Person quadrant elevates comfort. Its inhabitants are delighted by the permission above arguments give to sacrifice demands of pride, progress, and optimization. To the extent Last Persons value competence and integrity at all, they mostly see a single domain of getting what they want and a single constraint of continuing to feel good about themselves. Unlike psychopaths, whose relationship to competence and integrity could perhaps be described similarly, they are uncomplicated rather than unempathetic or conniving. They can love and care, but cannot give effectively at scale. They can sacrifice and demonstrate virtuousness, but cannot prioritize causes or honor. They can work hard, but cannot see the bigger picture or strive for greatness. Their primary motivation is to Be Happy.

Defense of Competence and Integrity

The crucial question isn’t about justifiability of specific actions or values – although most arguments correctly center on this: it is about the ethos of competence and integrity. The crucial conflict isn’t between Warriors, Pragmatists, and Idealists – although most battles are inevitably between them: it is between Last Persons and them all.

For all their differences, Warriors, Pragmatists, and Idealists value competence and integrity. They vary in domains they consider primary and in constraints they place on achievement.

They approach issues with an assumption that there is a domain-specific system underneath. Problems may stem from mistakes or inefficiencies that can be corrected or from trade-offs that may be reasonable. The central difficulty is development of competence to understand how things work and attainment of skills needed to make improvements. This challenge must be solved by individuals who can then rightfully expect recognition for their expertise and contributions. Every problem is a unique trial that offers important lessons.

This develops appreciation for how difficult and error-prone problem-solving is while emphasizing the importance of doing. It respects the outside view and grows sympathy for people in the arena.

The Last Persons approach proceeds essentially in reverse. It begins with individual desires and perceived unfairness. Problems may be blamed on anything diagnosable without domain knowledge. The central difficulty is making effective demands that accurately reflect desires and engage help. Good people contribute by exposing issues or sympathizing about them. Every problem is a generic annoyance that offers unique opportunities for commiseration and solidarity.

This develops appreciation for connections and justifications while emphasizing the importance of asking. It respects niceness and grows sympathy for suffering.

Protecting the ethos of competence and integrity doesn’t necessitate devaluing all that Last Persons do and believe. It demands keeping pride, truth, and contribution on a pedestal. It requires permission to judge and a path to teach high standards. And it compels concern with effects other actions may have on these over the long term.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Psychopaths offer an extreme example of this. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Orwell’s fictional account of the hapless Boxer in Animal Farm is based on the competence-focused Stakhanovite movement of the nascent New Soviet Man era. |

| ↑3 | Scott Alexander’s post on mistake theorists highlights the logic. |

| ↑4 | These days it is fairly common to be reminded – correctly – of contributions from flawed people and taken-for-granted jobs. But the offsetting impact of unwitting mistakes made by flawed people and contortions made necessary by their limitations are rarely mentioned. |

| ↑5 | Bruce Sterling cleverly distinguishes commendable frugality from risk-averse obsession with not making things worse by asking whether your dead great-grandfather is doing the task better than you. The goal should be to maximize your resource-adjusted contribution, not to minimize your resource use. |

| ↑6 | Engineers, for example, are susceptible to terrorism and conservatism. |

| ↑7 | Francis Fukuyama presents a compelling case for desire for recognition being a major driver of individual action and human history starting with The End of History and the Last Man through Trust and Origins of Political Order. His recent Identity offers a more compressed, updated, and accessible presentation. |

| ↑8 | See Irving Kristol’s lucid “Republican Virtue vs. Servile Institutions” in The Neoconservative Persuasion. |

| ↑9 | Early portion of The Existential Pleasures of Engineering offers an engaging account of such risks and the shift of focus towards them. |

| ↑10 | Fukuyama explores this in Trust: The Social Virtues and The Creation of Prosperity. |

| ↑11 | The Real Problem at Yale Is Not Free Speech offers a wonderful description of how detachment from reality and avoidance of responsibility are seeded, nurtured, and entrenched; and how the assimilated think, act, and perceive themselves. |

| ↑12 | The distinction between Being Somebody and Doing Something comes from John Boyd though my use of terms is a bit different. Boyd’s dichotomy always spoke to me yet felt off as a general model because it merges integrity and contribution into Doing Something. A goal like being a principled person has no clear home. Boyd would be more of an Idealist in my model. Still, I cannot resist the use of his terms. |

| ↑13 | A quintessential example of pragmatic self-sacrifice is acting without hope of recognition: “one can do a great deal of good in this world if one doesn’t care who gets the credit for it.” |

| ↑14 | I discussed the conflict between Being Right and Being Happy in Two Paths Towards Happiness. |

| ↑15 | The proud choice behind “unreasonable” values and efforts of individuals, and the importance of its recognition, comes through well in this review of Hillbilly Elegy. |