Accurate and coherent action hierarchies seem obviously necessary for productive action. How can haphazard everyday decisions lead to desirable long term consequences? How can incoherent models lead to effective strategies? How can uncoordinated action avoid mistakes? How can resistance to feedback lead to strong models and capabilities? If we don’t know where we are going, how can we expect to get there?

It is therefore immensely frustrating to see incoherent action all around us. From the smallest individual projects to the largest organizations and global concerns most action seems shortsighted and detrimental to its own goals. Furthermore, opportunities for disproportionate increases in effectiveness seem simple and obvious.

The cornucopia of potential improvements is at first baffling and then empowering. Who would have thought that basic insight could be so rare and valuable, that inexperience could be a source of vision? Unencumbered by limitations of obsolete technology, social norms, and past obligations visionaries can better see the flaws of existing structures and are well positioned to direct their improvement.

But even the simplest, most beneficial, and least contentious changes are resisted with greater fervor than visionaries thought possible. Some blame this unexpected resistance on lack of logic, but individual actions do tend to follow from their goals, models, and skills. Others blame individual action hierarchies: if they can generate such irrational behavior, then they ought to be replaced. But this obvious solution faces the same fate as the one that led to it: people vigorously resist overt attempts to influence their action hierarchies.

It is to the questions of why people do this and how it affects action and progress that we turn to next.

Complexity and Magic

An apparent feature of the action hierarchy is its complexity: the sheer number of levels, how many interactions there are at each level with models, constraints, capabilities, and how many roots of action and understanding are hidden from casual introspection. An attempt to fully expand the hierarchy makes even trivial tasks seem irreducibly complex, yet we regularly perform such tasks effortlessly and confidently. We accomplish this feat by replacing rigid specifics with flexible abstractions – with magic.

Magic steps in for the parts we’ve forgotten, taken for granted, misunderstood, or never thought about. It’s always ready to provide what is missing, to flow through the hierarchy and cohere it like glue.

Magic smoothes out the nuanced, outsources the difficult, and connects the disjointed. The foundational capabilities I discussed in the last post are a manifestation of magic. So are rules of thumb and social norms. So are beliefs that some parts of the hierarchy are obvious or trivial. So is reliance on others.

Magic allows us to believe that our action hierarchies are coherent, that we are justified to act confidently in the face of complexity. But it also makes us resist changes on which efficiency and achievement of shared goals depend. Many astute people thus locate magic at the root of problems and make it their mission to attack it.

But not only does magic prove resilient to attacks, the hierarchies of attackers turn out to themselves rely on magic. Part of the problem is this:

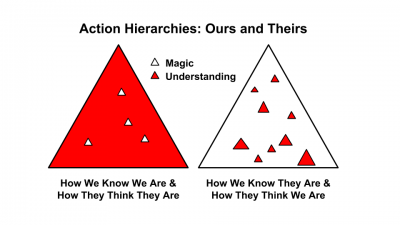

Both sides believe that their hierarchies are coherent and those of the other side are not. This isn’t just hubris or ill intent. Magic is how we reduce complexity of action hierarchies. To make sense of the hierarchies of others requires that we do more reduction over a shorter time period, and that we be more aware of it.

When faced with evidence that our logic is mistaken, our predictions inaccurate, our strategies ineffective we can readily acknowledge that we have some flaws here and there, but continue to believe that it all mostly ties together. We intuitively grasp that action hierarchies are complex, interconnected, and difficult to build and therefore resist rash corrections, especially when they are advocated by outsiders who are unlikely to share large parts of our hierarchy. We cannot trust that their solutions are compatible with our foundations and, in any case, we can readily see flaws and magic in their own hierarchies.

Our underestimation of the amount of magic in our hierarchies is real – the diagram could as well have been labeled Perception vs Reality – and magic does lead to many mistakes and limitations, but these facts aren’t enough to condemn magic or to dismiss its resilience to attacks as mere ignorance or irrationality. Magic is sticky because it is sometimes more true, sometimes more effective, and is, in any case, necessary and unavoidable.

Magic Powers

In execution, there is no state more precious than what is colloquially called ‘being in the zone.’ In this state our performance is smooth, certain, energized, and so far above the norm that we sometimes achieve more in those moments than in all the other times combined. Our focus zooms into the current action while the rest of the hierarchy feels clear and in synch. Clarity enables confident execution that uses our hierarchy to its fullest. Success in turn motivates and energizes us, fuels the positive feedback loop.

It feels magical. And, like magic, it tends to go poof the moment we think too hard about it, or something unexpected happens, or someone tries to add nuance. Magic helps our goals appear obvious and our models true, it tunes in our meta-capabilities, it enables our hierarchy to act as one – at least for a time.

Indeed, without magic we’d rarely start, much less complete, projects of any ambition. People frequently quip that if they’d known what was involved they’d never begin. Magic allows us to believe that we understand what it takes to reach even the most complex goals, that they are achievable, even simple. And it fuels perseverance, that stubborn desire to stay on course long after more grounded spirits have turned back.

Action depends on magical compression of already completed steps as much as on simplification of what’s ahead of us. Without it we’d constantly second guess our foundations, be overwhelmed by complexity, be paralyzed by the uncertain, unknown, and unknowable, be gripped by pessimism and prone to inaction. Instead, we naturally and effectively divide-and-conquer. Once we accept models, we treat them as truths. Once we accept goals and strategies, we treat them as optimal. Once we accept constraints, we treat them as involitable.

Our fundamental goals, values, models, and capabilities are rooted in long forgotten circumstances and confirmed by countless experiences. Connections between these truths and subsequent hierarchy components tend to be intuited during decisions and forgotten. At any time our thinking is dominated by concerns about a specific action; we got there without sensing flaws and therefore assume that all the other parts are correct.

The hierarchies that underlie our actions thus appear to us as cohesive, universal, and objective even when they are full of loosely connected layers of subjectivity and unexamined assumptions held together by pixie dust. But to fixate on this is to ignore that – much of the time – our focus on what’s directly in front of us is justified, compression encodes valuable truths, and the faith that our direction is fundamentally correct is essential for motivation and perseverance. The alternative to magic isn’t more effective action, but oscillation between fatalistic inaction and desperate rashness.

Magic compresses understanding that is too complex to be practically accessible otherwise. Traditions and rules of thumb are such a form of cultural memory: they encode evolutionary wisdom and make it approachable. They, of course, also encode falsehoods, but tend to be much more correct than they appear to those who’ve achieved magical simplicity by underestimating complexity. Kevin Simler offers an excellent exposition on the value of magic in his serendipitous recent post.

Science, technology, and specialization similarly compress complexity into magic. Modern action hierarchies thus still rely on genies who encode powerful truths together with destructive falsehoods. Most of us don’t pretend that we can replace these sources of magic with something easily comprehensible, don’t claim that they are false because we don’t understand them, and wouldn’t dream of discarding them.

We do occasionally get concerned when genies get temperamental. And some of us do find reliance on magic lamps alienating. But the alternatives merely substitute local, smiling genies for remote, robotic ones. Whether we depend on our GPS or on gas station attendants, we substitute magic for understanding. We are less capable and our use of magic sometimes backfires, but we can’t competitively accomplish much of anything without magic.

Social norms – such as expectations of politeness and conformity, or of a sympathetic ear for our complaints – are as much a form of magical technology as beliefs and computers. On closer inspection, they may seem inefficient or inaccurate; and they may externalize some of our responsibilities (such as unfairly burdening gas station attendants.) But because they are deeply felt to be true by most people, they offer a competitive advantage to hierarchies that optimize around their existence. They have proven themselves to be effective and will not be given up for mere promises of the greater good.

Magic earns its keep because it embodies complex truths, offers real world advantages, and enables motivated action.16/27/19 – For more, see this excellent Slate Star Codex sequence prompted by The Secret of Our Success.

Magic Rankings

I do not mean to suggest that all magic is equal – far from it. There is a significant difference between a blindly accepted belief and carefully worked out understanding that is compressed into a trusted theory or functional technology, between superstition and implicit knowledge developed through experience, between denial of evidence and respect for complexity. When people attack magic they are concerned with stubborn superstition, not with justified abstraction.

Unfortunately, they are difficult to tell apart. Contentious truths eventually turn into obvious, blindly accepted facts. Carefully worked out theories depend on assumptions. Ignorance and implicit knowledge appear equally illogical. Empirical evidence values measurable metrics and short-term results at the expense of black swans and long-term trade-offs. People have, of course, suggested solutions to challenges like these, but they have neither been agreed upon nor are amenable to quick evaluations that are necessary in practice. In practice, we more or less just attack magic.

Because magic is so important to learning, motivation, and action – and its benefits so rarely directly depend on its correctness – we’ve evolved to defend it naturally, passionately, and automatically – whether or not it is justified. From confirmation bias, to availability heuristic, to false consensus effect, to a slew of other biases it can seem like we are not only capable of, but are optimized for, the defense of magic.

Of course, whatever the value of confidence, reality is unconcerned with our internal state. Inaccuracies lead to ineffective strategies. Overdependence on magic dulls meta-capabilities. When magic is carelessly chosen, overused, or misapplied it results in incoherent, incompetent, and fragile action hierarchies. They accumulate dependencies, inaccuracies, and habits while allowing their capabilities and insight to atrophy until they are able to neither function nor understand the reasons why.

Although the visionaries overstate their case, they are correct about the poor state of most action hierarchies. They are substantially incoherent by their own standards, limited in accuracy of their predictions and effectiveness of their execution, almost entirely composed of genies and magic spells. Their strategies tend to be mechanical instantiations of poorly understood procedures. Their occasional insight and coherence centers on optimal arrangement of magic blocks, divorced from concerns about the price genies must extract to grant their wishes.

Even when magic is responsible for the poverty of action hierarchies, it is pervasive, necessary, and stubborn. We cannot hope to eliminate it, but perhaps we can move towards more accurate and effective types of it.

Magic and Communication

Most theories of progress pin their hopes, at least partially, on communication: parts of superior hierarchies are to be made explicit and relayed to others so that they can understand and merge them into their own hierarchies.

To communicate we first need to ‘get on the same page’, to agree to discuss the same part of the action hierarchy. At any one time a specific component of a specific action provides the default context for our thoughts. We tend to assume that others either have a similar focus or should. We do this because magic shrinks the rest of the hierarchy; and because we need to assume a level to communicate, just like we need to assume correctness to act.

Now that we have seen how massive hierarchies are, it should be obvious that even when two people are thinking about the same thing, they are unlikely to be focused on the same part of the action hierarchy. Convergence takes effort.

In theory, they can just ask ‘why?’ until they converge to high level goals or ask ‘how’ until they converge to fundamental capabilities. In reality, there are no easy ways to cross the seas of magic that tie hierarchies together.

Convergence is only possible in a space that is understood by both participants, such as where the same area is red in both hierarchies below:

Magical areas appear obvious or irrelevant; they can only be approached productively by building to them from a shared red space.

Convergence does not require truth or prove agreement. It is only the necessary first step for a productive conversation, but few conversations complete it.

As we saw earlier, almost everyone believes that their hierarchies are overwhelmingly red. We are convinced that we’ve already converged to a level, understood it, and are ready to proceed to the real conversation. Most communication thus never even talks about the same part of the action hierarchy. Instead, we talk past each other, climb up the hierarchy to find evil, climb down the hierarchy to find incompetence, or assume that the conversation is not in good faith.

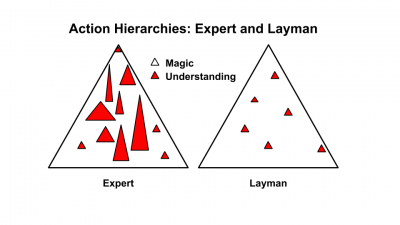

Furthermore, the less sophisticated party has an edge in such a debate; a concept related to Venkatesh Rao’s Curse of Development. The less someone understands, the easier it is for them to see real or imagined inconsistencies between distant parts of the hierarchy, to dismiss details as irrelevant, and to switch levels frequently. Conversations with motivated laymen, critics, and experts in adversarial communication are nearly impossible to pin down because they are so willing to jump between goals, models, values, constraints, capabilities, execution details, and all the levels between them. Magic encourages such powerful sophistry by making leaps seem like steps.

Careful and knowledgeable thinkers are both more exposed to level jumps and more debilitated by them. Explanation of specifics requires more assumptions, more words, and more precision than general statements. By the virtue of increased complexity, imperfections of language, and level-specific models it is easy for something like details of low level execution to appear to violate higher level principles.

These violations may be real-world concessions to imperfection, much like manners appear theoretically unnecessary and contradictory, but are actually required to oil interactions between imperfectly matched hierarchies. Or they may be illusory – mistaken for violations because of an over-reaction or lack of understanding. But in any case, the less someone knows the easier it is for them to dismiss insights – that may have taken years of work to achieve – as unimportant details.

To actually engage in such details, with all their nuances and interconnections, requires focusing on a specific concept and loading a significant amount of information. Because of this, the more someone knows, the more expensive and disorienting context switches become. It is easy to make a knowledgeable, genuine, and sophisticated person appear foolish and inarticulate simply by increasing the tempo and initiating level jumps as soon as they begin to speak confidently. Because of this, experts ultimately hire out such interactions or become more selective in their engagements – unless, of course, they happen to have the specialized skills required to play this game well and the interest to do so.

This isn’t just an argument against bad faith or layman hubris. The expert may well know more than the layman, but their hierarchy is still full of magic and the layman’s still isn’t a blank slate. Much contemporary magic is rooted in expert hierarchies and many visionary ideas come from layman’s oversimplifications. The larger issue is that the merging of hierarchies is inherently difficult and contentious; suggestions of simplicity rest on veiled, and unfounded, hopes of wholesale replacement of one set of magic with another.

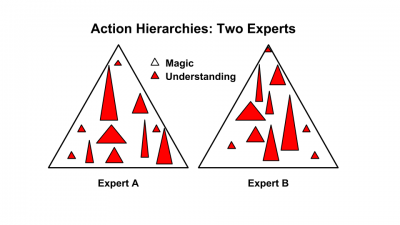

This is demonstrated by interactions between experts who, despite significant understanding and better capabilities, remain unable to converge to large scale truths:

The two experts in these diagrams have a significant, and equal, amount of understanding. They have better developed meta-capabilities as a result of having built such extensive hierarchies. They may be better at finding shared red areas, at explaining their position, at merging information, and at respecting context switch costs and keeping the conversation on the same level. But the amount of shared red space between them is still preciously small and they both want to drive the conversation towards their own red spaces.

Experts are stubborn because they are more knowledgeable about their red areas; they are more confident that they are correct and more careful to protect interconnections that cohere their understanding.

Action hierarchies thus become less amendable as they become more complete. Although the conversation between two experts may be more articulate, cordial, and superficially productive – at least when carried out in good faith – it rarely leads to substantive changes of opinion.

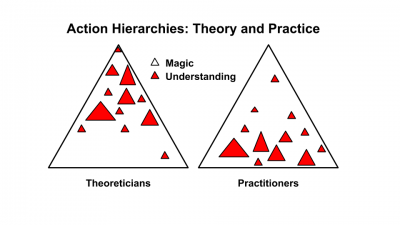

A special case of divergent expert hierarchies is the perennial conflict between theoreticians and practitioners:

In this diagram, as in the one above, both experts have a substantial, and equal, amount of understanding. But they have virtually no intersection of red parts because upper and lower halves of the action hierarchy have important practical differences despite being structurally the same.

Theoreticians prioritize consistency with high level constraints, have limited and uncertain feedback, and lean more on deduction, articulation, and argument. Practitioners prioritize physical execution, have faster and more reliable feedback loops, and lean more on induction, implicit knowledge, and experience.

As a matter of practical necessity, the two sides are forced to interact with, and depend on, each other, but there is plenty of tension. At extremes, theoreticians consider execution trivial and practitioners consider goals, models, and strategies obvious.

These tensions parallel the ones between System 2 and System 1 in our minds. We, as individuals, routinely face similar conflicts and often resolve them in incoherent ways, but we easily forget or justify our own choices while treating explanations of others with utmost skepticism.

The reality of communication is summarized by Wiio’s law:

“Communication usually fails, except by accident.”

Mutual understanding is a rare, fortunate event, not the norm.

But before complexities of teaching and communication can even begin to matter, we need to figure out what to teach, to select which hierarchies are superior.

In Search of Coherence

At first glance, successful hierarchies and coherent explanations are all around us. Unfortunately, because most hierarchies are so poor, expertise at even a few capabilities, accuracy of even a few models, coherence in even the smallest parts of the hierarchy can provide enough of a competitive advantage for real-world success.

Because hierarchies appear more coherent and complete than they really are, the winners fill self-help sections of bookstores with insights to their success. Theoreticians create case studies to demonstrate that the components winners possessed are the key.

But even when genuine and well presented, these insights are specific to the individual. Whatever magic they tamed, whatever obstacles they overcame were specific to where they were stuck and were contingent on the rest of their action hierarchy – which they consider obvious thanks to magic. Others are unable to successfully apply these formulas because they are stuck elsewhere and these insights are already obvious or not yet relevant to them.

Furthermore, effectiveness of a partially coherent action hierarchy is a function of a fortuitous match with circumstances and even greater confusion elsewhere: the same individual may be unable to apply their own formula to different circumstances. As attempts at replication fail and flaws in the action hierarchy lead to mistakes, theoreticians turn negative outcomes into case studies and demonstrate how important the missing components of the hierarchy are to success.

We end up with shelves full of books and ample empirical ammunition to support the importance of every portion of the action hierarchy. But while champions of various parts compete for supremacy and the public eagerly tests out one potion after another we remain no closer to a definitive secret to success.

The reason is alluded to by Arthur C. Clark’s third law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Coherent hierarchies are, in essence, a form of technology so we can get the challenge of action version with a simple substitution:

“Any sufficiently coherent action hierarchy is indistinguishable from magic.”

There has never been a time when magic, or technology, did not float in a sea of snake oil. The combination of tremendous appeal and limited understanding leads to a slew of cargo cult hierarchies, built by everyone from callous swindlers to well-meaning inventors. As with all incomplete hierarchies, we happily – and often subconsciously – connect the dots with magic, whether our own or someone else’s.

Coherent hierarchies make decisions obvious, execution smooth, action energetic and motivated. They make success seem simple. But just like a machine does its magic through reliable execution of complex strategies in service of defined goals, so do coherent hierarchies generate their results through a large number of correctly made choices. There isn’t a subset of hierarchy components that makes it work: you need them all.

Imperfection in any part of the hierarchy carries costs, which makes effectiveness of any prioritization temporary and situation specific. But because all magic looks equally true, we quickly extrapolate generic lessons from short-term, specific successes. We continue to jump from bottle to bottle, to explain away failures, to search for the magic lamp.

Coherent action hierarchies look like clean magic, but are built with years of deliberate practice, risk-taking, and failure, with their fair share of blood, sweat, and tears. There is no easy, trade-off free, or guaranteed path to effectiveness, but at every turn there is yet another guru promising a way to reach the destination without toil. But without the understanding to make the thousands of correct choices, big and small, we can neither succeed nor recognize our reasons for failure.

Complexity and magic makes genuine understanding as difficult to recognize as to communicate, while making its appearance easy to fake.

To sidestep this difficulty, we can develop hierarchies from first principles. Instead of depending on being taught, we can prioritize self-learning through building. When we are intimately involved in every decision we have less reason to worry about misunderstandings, mistakes, and magic than when we rely on others.

Indistinguishable from Magic

Building coherent hierarchies from first principles is immensely difficult, impractical, and correspondingly rare. But it is possible: accurate, cohesive, capable, and adaptable action hierarchies do exist. Although these hierarchies are much more expensive to build, their power increases rapidly as they approach coherence. Those who possess, or approach, them gain a long-term advantage that is so incomprehensible that they can seem like forces of nature, their actions indistinguishable from magic.

These individuals – and this level of coherence is invariably confined to a single person – possess hierarchies that are as pure and full of understanding as is possible. They are the ultimate experts and represent the best, if idealized, chance for education.

Unfortunately, possession of a coherent action hierarchy, and the corresponding ability to act effectively, is only one of at least four components of mastery necessary to teach. There is also the ability to make the action hierarchy explicit, the ability to explain it to another person, and the ability to turn that person into an independent master. Although someone who is competent at more of these aspects is certainly a greater master, each of them is difficult to achieve and relies on substantially independent skills.

Before a hierarchy can be explained it must be made explicit. Some conflate understanding with the ability to explain and claim that if this step isn’t trivial then the teacher doesn’t actually possess a coherent action hierarchy. But surely, the ability to do is a greater proof of understanding than the ability to explain!

Skills of articulation and action are not only separate, but are often in conflict. Hierarchies grow by turning understanding into high level capabilities, into magic. Accurate understanding is important for ultimate coherence, but we do not know what is accurate until the hierarchy proves itself. To reach this capacity to prove, we focus on doing over explaining, on tuning models, feedback management, and capabilities to function on an intuitive level. The ability to do rests on compressing even the most elaborate explicit understanding into implicitly understood axioms.

The process of hierarchy creation isn’t linear. We discard, add, and modify assumptions as we act. Much of the time, we don’t know that we are onto something until the web of adjustments and magic becomes too complex to be untangled. It is to get a handle on this process that so many thinkers keep journals and the scientific method demands careful recording.

But the ability to articulate is still limited by practical capabilities, forgotten foundations, and issues like the use of language. Complex systems with feedback loops are extremely difficult to make explicit for even the best writers. Today we can encode such systems into computer models, but these simulations are simply another form of magic, with their own implicit assumptions.

As we saw in the last post, successful hierarchies aren’t even complete as a rule: we fill them in during execution. Coherent action rests not merely on accuracy, but on well tuned meta-capabilities and feedback processing, on exactly the types of systems that demand simulations to be grasped.

Thus even hierarchies that were carefully built from first principles end up full of magic by the time they’ve proven themselves effective and coherent. Explicit explanations are constructed in reverse, whether by teachers or doers themselves. Even when expertly done, they lack the implicit assumptions and contingent factors of dynamic hierarchy creation and thus are better at explaining what has happened than at guiding action. It isn’t surprising that many doers cannot explain and that many explainers cannot do.

As difficult as it is to make an action hierarchy explicit, it is only the first step. We next need to be able to explain it to another person, which demands overcoming all the challenges of communication: we need insight into their mental state, the ability to build up the hierarchy using their models, goals, and skills, and the ability to keep the conversation on a single level long enough for this building to occur.

Even when successfully relayed, explicit understanding does not assure coherent action, as we just discussed. Masterful, independent action requires us to replicate the slow, inductive process of hierarchy formation, to reconcile new information with existing hierarchies until correct choices come about intuitively, as if by magic. There is a reason that mastery resists articulation, requires much deliberate practice, and was historically passed on through long apprenticeships that began at a young age.

So even if we were able to build a legitimately coherent and effective action hierarchy, it would remain nearly impossible to teach to others. We could instead convert such a hierarchy into processes that are accessible without understanding: checklists, automation, rules of thumb… In other words, we could turn it into magic. Such processes are, in fact, part of the reason why magic contains real truths and enables effectiveness, even after it ossifies and disconnects from its original purpose.

Direct Action and Soulmates

Alternately, instead of teaching, we could use our superior action hierarchy to directly drive progress. One of the most powerful aspects of modernity is the ability to scale massively without synchronizing with a large number of people. This not only magnifies the competitive advantage of coherent hierarchies, but allows them to remain coherent at much larger scales. The competitive advantage of superior hierarchies has never been as scalable, as convertible into results by as few as a single person. But an individual remains limited in what they can accomplish, even with the best of technology.

Expansion requires teaching or procedures, which run into the limits of scalability. One ray of hope is to instead unite with people who already understand: people who happen to substantially share our action hierarchy can act as we would without the difficult and uncertain process of communication and practice. Like soulmates, they get our action hierarchy without us making it explicit.

Modern technology is again essential to shrinking the world enough for soulmates to be found. But, although easier than merging of hierarchies through communication, identification of matches remains difficult and error-prone. Much drama in creative work centers around the quest to find soulmates and the disappointment when they prove to be imperfect copies of ourselves.

Even when soulmates are fortunate enough to find each other, they cannot stay united forever. Their tasks diverge as scope grows, and since action hierarchies are modified by execution, their hierarchies diverge as well. Different tasks depend on, and develop, different models and capabilities which aren’t all equally compatible with the rest of the hierarchy. Even something as simple and inevitable as increased specialization into either theory or practice has profound effects.

Theory and practice face different practical challenges in all hierarchies. Coherent hierarchies achieve unified action through a strong coupling between them. But as specialization increases and external influence grows, pressure on their differences intensifies and they begin to separate.

Practitioners use their implicit knowledge to adjust plans and make things work. This low level illegibility frustrates theoreticians who adjust strategies for expected disobedience of practitioners. Mutual trust, respect, and understanding erode. It isn’t a coincidence that most vicious fighting occurs among those who mostly agree, that former allies frequently split into warring factions.

Soulmates offer the best chance at growth while maintaining coherence, but they are difficult to find and even more difficult to keep together. Furthermore, some skills are too incompatible to be found in soulmates. Much real-world growth, and plenty of insight, occurs by working with those whose hierarchies overlap ours a bit despite being incompatible. The benefit of trader values is that they enable effective cooperation without soulmates.

But such pragmatism decoheres existing hierarchies. The same external pressures that force ad hoc compromises become an essential, internal part of the organization. As independent agents that make up the hierarchy more overtly seek individual ends, procedures and checks replace shared models and goals. Internal politics and competition handcuff organizational agility and increase its cost of action. The organization becomes less efficient or even completely captured by its components.

There are, of course, better and worse ways to tackle the increasing costs of fighting entropy that come with pragmatic growth; perhaps we can even design for it from the start. But they all necessarily sacrifice the simple beauty and efficiency of a coherent hierarchy that drives so many impassioned arguments for perfect worlds.

Conclusion

Over the last few posts I’ve tried to show how complex action is and how difficult it is to build and maintain coherent action hierarchies envisioned by theoreticians. Action consists of a fantastical number of components, levels, and interactions. The origins of these components and their arrangements are presumed to be shared, factual, and obvious, but are variable, contradictory, and inaccessible. The entire hierarchy morphs as it acts, often in ways that aren’t predictable.

On a daily basis we are astounded by incoherence and incompetence all around us, but instead of making us appreciate the challenge of coherent action it makes us believe that improvements are a matter of correcting simple and obvious mistakes. We readily see flaws in actions of others, but fail to see that nearly all hierarchies, including our own, are closed to easy modification or explanation. It appears otherwise because we focus on small parts of a hierarchy and treat the rest as obvious or irrelevant.

We are quick to explain inability to agree as a matter of competence or morality when much disagreement stems from conversation on different levels, with different assumptions about what is trivial and what is important. With experience and good faith these differences become easier to see, but remain nearly as difficult to overcome.

Coherent hierarchies are as powerful as strategists envision, but even when they are achieved they remain fragile to growth, time, and change. Coherence, longevity, and impact on the external world are in tension that cannot be overcome with plans or skills. Actors must make pragmatic trade-offs and optimize around imperfect hierarchies, which assures that attempts at large scale convergence will perpetually face a moving target and vigorous resistance from stubborn and powerful opponents.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | 6/27/19 – For more, see this excellent Slate Star Codex sequence prompted by The Secret of Our Success. |

|---|